As discussed in Alexeyeva, World War II produced feelings of doubt in the people of the Soviet Union. A country taught to believe they were invincible saw with their own eyes that they were not. Not too long after the fact, Stalin died in 1953 and the country mourned. Many might be surprised to hear that the Soviet Union cried over the death of a seemingly oppressive leader; however, they knew no other life and it was ultimately the end of an era. This postwar society gave rise to a hedonistic lifestyle, but this is not unique to the Soviet Union. The same thing could be seen both in postwar America and postwar Germany, where older generations were shaking their heads at the new music and culture developing. However, this rise of a hedonistic lifestyle in the Soviet Union was unique due to its growth out of a repressive regime that prevented influence from outside and its lack of accessibility to all citizens in Soviet society.

In Edele’s “Strange Young Men in Stalin’s Moscow: Birth and Life of the Stiliagi,” it is established that the Stiliagi are not the majority: they are the privileged, middle class men of society. What they were lacking was not money or access to goods; they were lacking the freedom to express themselves. For example, they sought a secure sense of gender for themselves. Because masculinity was tied to military service under Stalin and these young men were not of age to serve at the time, they had to look elsewhere. Being they could not imitate veterans, they found they could imitate the western style of dress. This extended into Western ideals of fashion, hair, dance, and speech. The Stiliagi soon transitioned into the Shtatniki, but the core idea was the same. The goal was to emulate American fashion. However, the party took this expression of American style as un-Soviet and “rootless cosmopolitanism.” Unlike the truly struggling people of the Soviet Union, this group of people appear to be purely rebelling from a psychological standpoint and had the opportunity to do so due to their privilege in society.

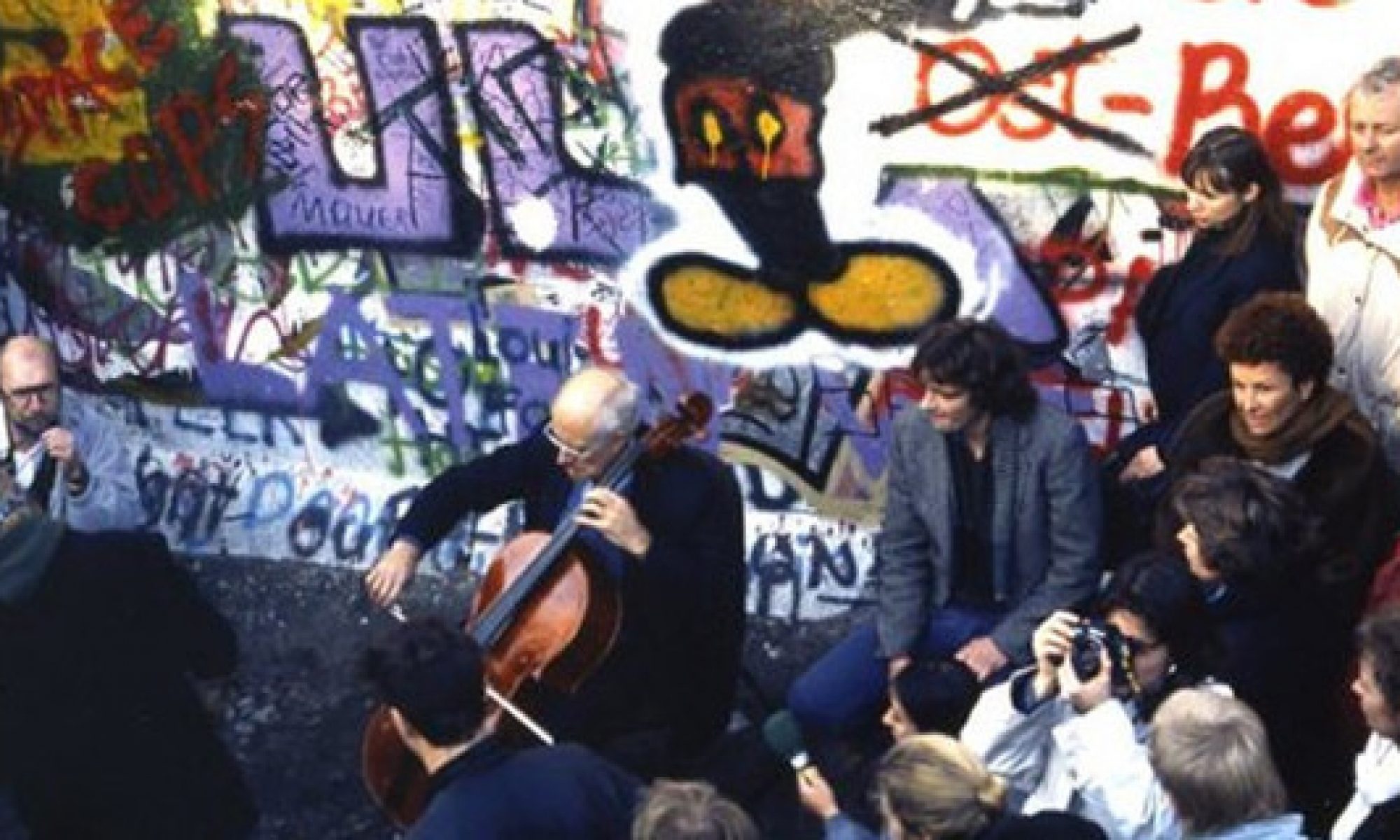

While the Stiliagi and Shtatniki were reaching towards Western fashion, musicians reached towards the West as well. The music was very different than previous socialist realism that was desired by the regime. Some of the music was emotional, even sad, and others have strong pop and jazz influences. The music was clearly not celebratory of communism, with the second song even criticizing the regime having lyrics referring to the soldier as paper “dying under fire for nothing at all.” In many ways, this new music was simple with few instruments and one voice. The lyrics told a message rather than what we saw in propaganda music like “Life is Better,” designed to support the government instead of being an expression of the individual. This new music was another way in which the people of the Soviet Union were slowly growing their own individual identity following a collectivist government.

- Why was the Party not able to once again repress music as they did before?

- Why did the people of the Soviet Union mourn Stalin’s death?

- Why do you think the people were shocked to find out Stalin was a criminal knowing how they personally were living?

- Why out of all of the genres did music go in the direction of guitar poetry?

- Why do postwar societies often turn to hedonism?

- If the Stiliagi was more reserved for the privileged middle class, what were the poor doing? Were they turning to the West as well?

- Do you think the result of the Soviet Union would have been different had following Stalin’s death, they did not strive to continue to repress Western influence or were their doubts in communism already too strong?

- Why do you think some when given the opportunity to study anything (Thaw Generation) chose to study Lenin and Marx?

- Why were women seemingly left out in the readings and music/How did gender play into this discussion?