Please check here to see when you signed up to meet with me about your midterm project.

Reading Assignments for Kater’s Composers of the Nazi Era

Check here to see which chapter you signed up to read for Tuesday’s class: http://www.musicpoliticsf19.theleahgoldman.com/kater-composers-of-the-nazi-era-reading-assignments/

Syllabus Adjustments for Unit II!

Dear Musical Politicians,

Thank you for your great work last week! I gather that some of you are having a very stressful semester. In the interest of continuing to have substantive and penetrating discussions of our materials without overburdening you, I’ve made some adjustments to the reading and listening assignments for the rest of Unit II. Here is what you need to cover over the next two weeks:

Tues, Oct. 1

Kurt Weill, Three-Penny Opera (full film)

Do not read: Michael Kater, Different Drummers

Thurs, Oct. 3

Albrecht Dümling, “The Target of Racial Purity: The ‘Degenerate Music’ Exhibition in Dusseldorf, 1938”

Pamela Potter, “What Is ‘Nazi Music’?,” The Musical Quarterly, 88:3 (Fall 2005), pp. 428-455 [*Please Note! This was originally assigned for Oct. 8. We will read it on Oct 3 instead of Potter’s article “Attempts to Define ‘Germanness’ in Music”]

“Letter from Furtwängler to Goebbels,” Ten Principles” and “From Hitler’s Speech” in The Arts In Nazi Germany

Tues, Oct. 8

Michael Kater, Composers of the Nazi Era

Note: This is the only reading assignment for this day!

Thurs, Oct. 10

Same as before. For Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, you only need to listen to the 4th movement.

I will go over this with you in class on Tuesday. Thanks again for your hard work, and please let me know if you have any questions.

Blog Post 09/23/2019 (Callie)

Cabernet music in Germany under the Weimar Republic was so vehemently defined by the censorship of the government that it, as a genre, didn’t ever have a fair chance of recovery (Jelavich, Peter. “Berlin Cabaret”). Much like we saw in the Soviet Union, cabernet music became limited in view and was a tool used to serve the government’s ideological views and goals. I found it interesting that the music seemed to be just as controversial in the Weimar Republic as it was during the Soviet Union, but for differing reasons. In Germany music was controversial because some people thought that upbeat music during the war was not appropriate because of the severity of the times. However, others thought that music proved a good distraction because people needed something that took their mind off of the horrible happenings around them (Jelavich, Peter. “Berlin Cabaret”). The shows were also controversial because they were primarily focused on what was going on at the time, reflecting the travesties of war, but they still had very blatant nationalist undertones. I think that these nationalist views cause music to lose its true purpose, which it to be a truly expressive piece of work. Although I haven’t yet heard any of the cabernets from this time I assume they will be similar to the lackluster musical pieces from the Soviet Union. While these two regimes were different in many ways they both impeded on freedom of expression in music. Artist who were dubbed anti-nationalist weren’t well received. “When the Old Motor Beats in Time Again,” is a perfect example of a non nationalistic piece (Jelavich, Peter. “Berlin Cabaret”). In class I think we should discuss this piece further, and try to talk about why a musical piece like this is so important and what impact it had on society and the artist who created it.

Jelavich, Peter. 1993. Berlin Cabaret. Studies in Cultural History. Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=nlebk&AN=282596&site=ehost- live.

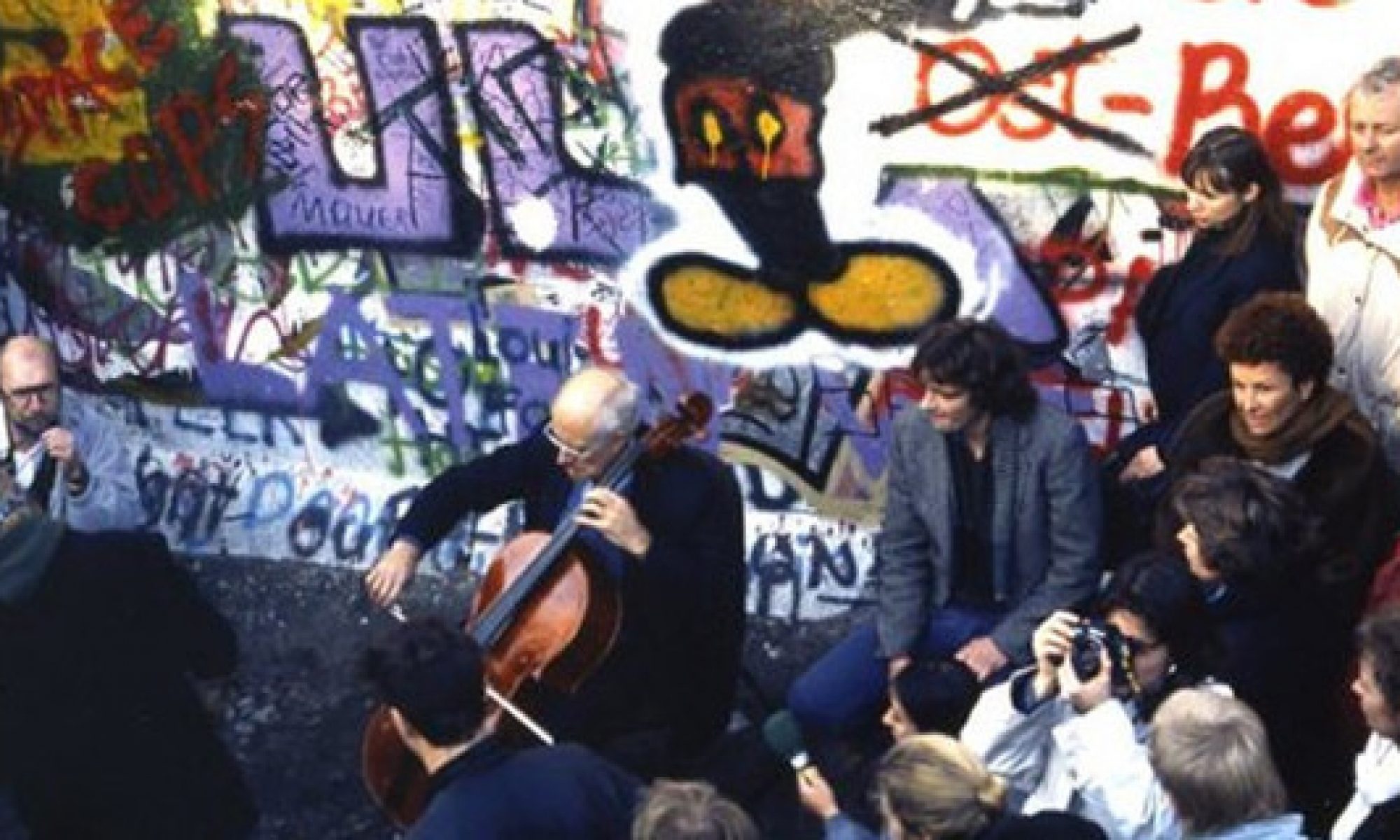

Welcome, Musical Politicians!

Welcome to HIST 315: Music and Politics in 20th c Europe! Whether you’re a musical politician or a political musician, I hope you’ll enjoy our journey together this semester and engage deeply with the themes and materials in this course. Over the course of the semester, we will explore the ways in which a variety of historical actors have created and used music for political ends in Europe across the 20th century and into the present. Working thematically, we will delve into four major moments when the politics of European music attained critical importance: the Soviet Union under Lenin and Stalin, Germany in the Weimar and Nazi eras, the youth and protest movements active across Cold War Europe in the 1960s-1980s, and our current moment of globalized culture. Along the way, we will explore how authoritarian régimes have tried to harness music to serve their purposes, and how and why composers have complied with or resisted such efforts. We will also consider the perspectives of composers and songwriters who sought to use music to make a political statement and discover how music influenced the thinking of protest leaders and disaffected young people on both sides of the Berlin Wall. Turning to the present, we will examine how musicians have tried to heal the rifts of the 20th century and think critically about what has been gained and lost in the process. Most of all, we will confront the indeterminacy of musical meaning and reflect on how that has influenced each of our case studies. This course emphasizes close reading, careful listening, creative thinking, and vibrant discussion. No prior musical training is required; we will work together in class to develop our own vocabulary for discussing musical works. Open minds and spirited participation are encouraged!